Celebrating Leo Marx on his 100th birthday

Over 40 years, the influential historian helped build MIT’s Program in

Science, Technology, and Society into a world leader in the field.

The Lackawanna Valley; c.1855, painting by George Inness

“For over four decades, Leo Marx’s work has focused on the relationship between technology and culture in 19th- and 20th-century America. His research helped define the area of American Studies which understands scientific and technological activities in the context of broader American society and culture.”

Commentary

by the MIT Program in Science, Technology, and Society

Leo Marx, William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of Cultural History Emeritus, was born on November 15, 1919, in the family apartment at West 110th Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam Avenue in Manhattan.

This year Leo Marx, his friends, and his family celebrate his 100th birthday at his home in Jamaica Plain, where he lives in a two-family house shared with his daughter and her family.

In between these two dates Leo Marx — who would become a renowned scholar, teacher, and driving force in MIT’s Program in Science, Technology, and Society — saw a great deal of history:

in New York City and Paris, where he was raised by his mother with the help of some of her French relatives after the early death of his father; in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where he earned his undergraduate degree in History and Literature at Harvard; in the South Pacific where, at the age of 22, he became captain of a sub-chaser, the smallest commissioned ship (25 men) in the Navy; back at Harvard, where in 1950 he got a PhD in a new field, History of American Civilization;

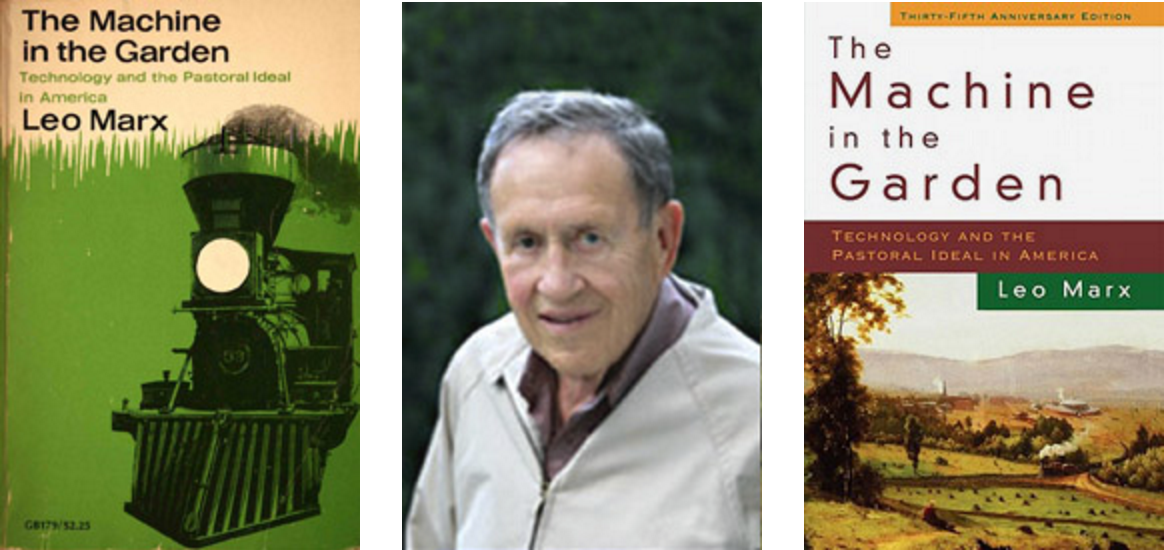

in suburban Saint Paul, Minnesota, where, as a self-proclaimed “effete Easterner,” he was “tested for membership in the real America” as he set off to teach 8am classes in winter temperatures of minus 20 degrees F; in the English village of Oxton, as a Fulbright scholar at the University of Nottingham in the late 50s, where the winter temperatures were not so frigid but central heating was absent; and in Amherst, Massachusetts, where he and his wife and three children settled for 18 years, and where Leo published in 1964 his much-revised dissertation under the title The Machine in the Garden.

The Machine in the Garden

The Machine in the Garden, or “MITG” as Leo would shorthand it, made a splash in intellectual history that still ripples. It got immediate attention for highlighting American writers who would have not been much read nor taken seriously in Britain or France. Another reason MITG got attention is its subtitle: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America. The pastoral ideal goes back many centuries to Greek and Roman classical poets, especially Virgil. The concept of technology — still new and relatively untried in postwar America — was then generally connected with topics such as employment, engineering, management, warfare, and production. There was some inkling that it had to do with a larger history, but what was the relationship? In any case, technology certainly had nothing to do with literature.

Leo Marx challenged this assumption.

What makes American civilization distinctive, he shows in MITG and other works, is the strength of the pastoral dream, encoded for centuries in Western literary works, that it stimulated. The wide-open American landscape, in all its expansiveness and richness, seemed to incarnate the imagined world of Virgil’s Eclogues. But the American landscape also awakened dreams of a final mastery of nature. In the midst of the woods of Walden, Thoreau hears the train whistle. Setting forth in a whaling vessel, Melville’s Captain Ahab obsessively hunts the white whale that has wounded him.

To this day, American life cannot be understood without reference to a fundamental conflict between pastoral dreams and machine dreams. In the American experience, as Leo Marx explains, literature and technology have everything to do with each other.

“At this point in American history it’s unimaginable to talk about anything of substance without talking about technology, the environment, and the American dream. This book was out in front. It’s about environment and technology before those two words became defining words of the history of science and technology.”

— Rosalind Williams, Professor of the History of Science and Technology, Emeritus

Marx at MIT, 1976-2015

In 1976, the life story of Leo Marx intersects with the institutional story of MIT. An extraordinary group of MIT citizens — Jerry Wiesner, Walter Rosenblith, Elting Morison among them — had decided that MIT needed to have the capacity in research and education to understand technology not just in instrumental ways, but in its most expansive, adventurous dimensions. To that end, they founded the Program in Science, Technology, and Society (STS), and in 1976 invited Leo Marx to join the faculty as the William R. Kenan Jr. Professor of American Cultural History. The invitation remains a pivotal moment in the history of MIT.

This was also a turning point in the life of Leo Marx. He soon realized that he could not keep teaching at MIT the way he had at Amherst College. He had some excellent students, both undergraduates and later some graduate students, for whom the class discussions and comments on their work were life-altering. But relatively few students at MIT were interested primarily in literature. So Marx gradually shifted his scholarship to other topics, especially to what became known as environmental studies. He continued to teach in and help shape MIT’s STS program for 40 years, first as a professor and then, after a mandatory retirement, as a senior lecturer between 1990-2015.

“Machine in the Garden examines the difference between the ‘pastoral’ and ‘progressive’ ideals which characterized early 19th-century American culture, and which ultimately evolved into the basis for current environmental debates.”

— Oxford University Press

The reading lists for his classes continued to emphasize imaginative literature, both past and present, as sources of evidence and insight into the role of technology in American experience. An article he published in Technology and Culture in 2010 explaining why technology is a “hazardous” concept was for many years among the most-cited in the history of the journal.

As the 20th century has rolled into the 21st, the concept of technology has become at once more dominant and more confined. More dominant, because all of history is increasingly defined as technological change; more confined, because the meaning of technology has been reduced to digital devices. The pastoral dream has receded as machine dreams have expanded. For over four decades at MIT, Leo Marx has reminded us that the most accurate, sensitive evidence of such events of consciousness — these major changes in how we think about technology, history, and humanity — may be found in imaginative literature.

Thank you, Professor Leo Marx — and Happy 100th Birthday!

SUGGESTED LINKS

Leo Marx

Bionote at STS Program

MIT Program in Science, Technology, and Society

Website

Books by Leo Marx

The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America (OUP, 1964)

The Pilot and the Passenger: Essays on Literature, Technology, and Culture in America (OUP, 1988)

Editor (with Merritt Roe Smith), Does Technology Drive History?: The Dilemma of Technological Determinism (MIT Press, 1994)

Editor (with Bruce Mazlish), Progress: Fact or Illusion? (University of Michigan Press, 1996)

About The pastoral genre in literature

Archive publications

3 Questions: Rosalind Williams, Bern Dibner Professor of Science and Technology, emeritus, on The Machine in the Garden

MIT symposium honors 50th anniversary of The Machine in the Garden

Leo Marx wrote The Machine in the Garden: Technology and the Pastoral Ideal in America in 1964, before cell phones, the Internet, and computers became omnipresent in American life. Yet today this work — centered on the tensions nineteenth century authors saw as shaping American life — remains as relevant as ever.

Webpage prepared by SHASS Communications

Office of Dean Melissa Nobles